In 2014, it was revealed that the authors of the Thug Kitchen, a best selling cookbook utilizing basic ingredients, colloquial Black English, and gangster tropes, were white identified. To begin, I believe their intentions were good. Similar to the Vegan Black Metal Chef and the Vegan Zombie, Thug Kitchen probably had hopes of making veganism appear fun and culturally relevant.

Heavy metal musicians, however, are not a disenfranchised group,1 and zombies are not even real. “Thugs,” however, refer to a very real, very marginalized group of people. In American society,2 “thugs” are profiled and assaulted by police, mass incarcerated, stigmatized, and otherized. Oftentimes, their lives are cut short as a result.

These experiences are wholly divorced from that of the white middle-class authors of Thug Kitchen, making this white appropriation of Black culture for the profit and amusement of white audiences a form of literary Blackface.

What is Blackface?

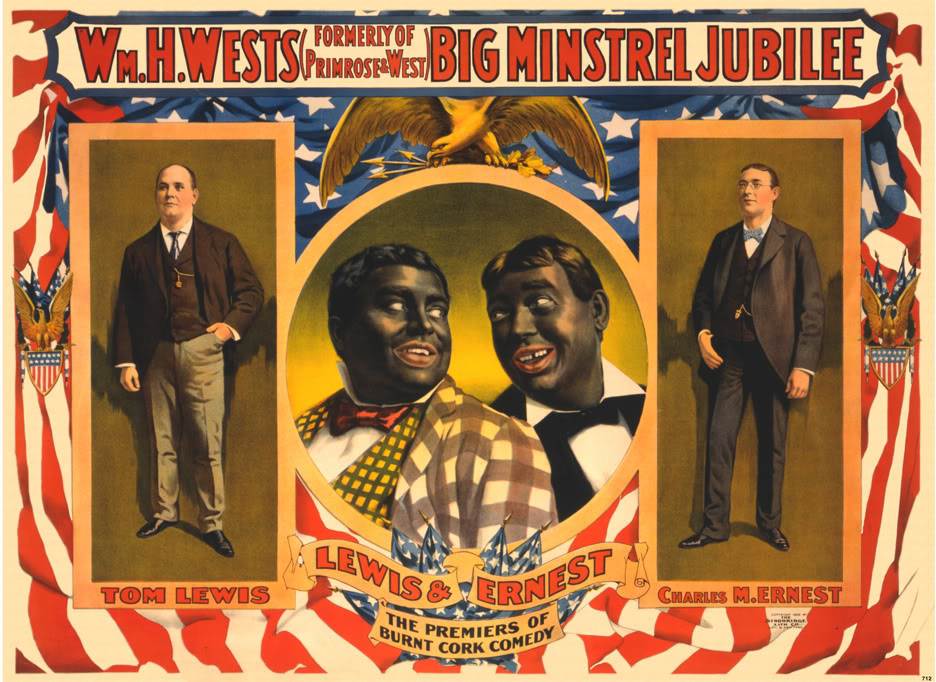

Blackface is present when whites represent themselves as Blacks for the amusement of white audiences. Historically, white entertainers would paint their faces and change their dress accordingly, but Blackface more generally relates to the use of nonwhite cultural stereotypes for whites by whites.

Blackface reflects a white legacy of entitlement and control over nonwhite spaces. It is problematic because whites pull on cultural items of value from the safety and comfort of their spaces of privilege while leaving structural discrimination in tact.

As an example, consider the popularity of Black jazz music among young whites in the early 20th century. Whites audiences and white jazz bands enjoyed Black culture in white spaces, while Americans of African descent suffered the Jim Crow violence of enforced poverty, segregation, voting disenfranchisement, and lynching.

By way of another example, consider the mass extermination of Native Americans in the 17th-19th centuries compounded by poverty, mental illness, suicide, and environmental injustice that persists today. Despite this unimaginable state-imposed oppression, whites of European ancestry idealistically lay claim to native geneology, proudly display tattoos of sacred indigenous symbols, and enthusiastically defend the “Redskins” team name and logo as respectful of native culture.

The Thug Cookbook enterprise is supposed to be humerous because it showcases white people “acting Black.” By extension, being nonwhite is marked as funny because nonwhite culture is supposedly ignorant, primitive, and uncivilized. The cultures of people of color are thus usurped for the entertainment of a presumed white audience, but there is a complete disregard for the dangerous reality of white supremacy in which this minstrelism will be interpreted.

Thug Politics

The rhetoric of vegan Blackface is problematic because “thug” is an extremely politicized word. For those who must live under the label, it can be a matter of life and death. To be labeled “thug” in white America means to be denied opportunities, civil rights, and fair life chances.

“Thug” politics also influence the epistemologies of white Americans. For instance, the murder of young teen Trayvon Martin was deemed acceptable to many because this young, unarmed man walking home from the store with snacks was perceived to fit the thug profile. Martin was young, black, male, in a hoodie, and in a white neighborhood. For this, he was killed.

“Thug” has become the new n-word. It is a means of referring to race without actually mentioning it. It a “color-blind” modern society, it maintains the cultural language about Blackness as a public threat.2 “Thug” acts as a racial identifier. It also becomes a qualifier. We are more likely to believe that thugs are innately deserving of whatever institutionalized violence is enacted upon them. Subsequently, there is no race-neutrality to thug rhetoric. It works to maintain a system of violence against people of color.

Vegan Blackface

Thug symbolism cannot be disassociated from a long and ongoing history of white supremacy, of which the Nonhuman Animal rights movement has played a part. Early anti-cruelty efforts were framed in white supremacist, nationalist terms. Despite the fact that many activists of the 19th and early 20th century were also heavily involved in human rights causes, they levied humaneness as a means of civilization. Make no mistake, this framework was (and is) highly detrimental to nonwhite, indigenous, and immigrant groups. There are thriving vegan communities of color today, but the mainstream vegan movement continues to be white-dominated in both theory and practice. This documented problem with racism makes vegan Blackface all the more dangerous.

Just as it is inappropriate for whites to wear indigenous headdresses to music festivals or wear sombreros with ponchos to Halloween parties, it is also unacceptable to play “thug” to sell books, t-shirts, or other vegan merchandise. This is especially so when the dominant ideology of the vegan movement centers the white experience and has historically been used to uphold white supremacy.

Notes

1. It has been suggested that the heavy metal genre actually appropriates African, Asian, and Middle Eastern music to some extent, as well as having historical ties to racist ideology.

2. UK readers may have a different contemporary understanding of “thug” than Americans, but it is important to note here that the term derives from the Hindi word, “thugee,” and Indians branded as “thugs” were violently oppressed under British colonial rule.

3. Other communities of color are also impacted by thug politics.

This essay was originally published on September 30, 2014 on The Academic Activist Vegan.

Readers can learn more about racism in the Nonhuman Animal rights movement in my 2016 publication, A Rational Approach to Animal Rights. Receive research updates straight to your inbox by subscribing to my newsletter.